All Too Human

During my visit to Halifax, Nova Scotia on April 14-15th, 2012 for the Titanic 100 commemoration, I met numerous people, young and old, from different ethnic backgrounds and without necessarily a direct relationship to any Titanic victim or survivor, who flocked from all corners of the globe, to be part of this special remembrance. Some were die-hard Titanic fans, fondly known as “Titaniomaniacs” and some were novices just like me. Notwithstanding their knowledge base disparity, both groups share, even one hundred years later, an unrelenting fascination with Titanic.

When first launched in Belfast, Ireland on the 31st May 1911, Titanic was the largest and heaviest moving man-made machine built to date. When first laying eyes on the mammoth like vessel in the Belfast shipyard, awestricken visitors felt they were witnessing history in the making. This complex and ancient relationship between Man and Technology, perhaps encrypted in human DNA and epitomized by the creation of Apollo 11, the spacecraft that landed the first humans on the moon, has always been both captivating and enthralling. Add to this model of Man’s ability to master his environment, the ostentatious grandeur and unrivalled luxurious interiors ever found on a cruise liner, no wonder why Titanic instantly became known as “The Ship of Dreams”.

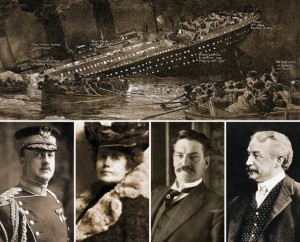

And glaring in our collective memory, is the hubris of the Titanic builders who boasted it was unsinkable and the cruel irony that it sank on its maiden voyage. Affirming Man’s fallibility and powerlessness in the face of Mother Nature, deceitfully portrayed by a glistening iceberg, the Titanic tragedy is a reminder of how small we are. In the vastness of the mighty ocean and under an endless dark sky studded with a myriad of stars and distant planets, the sinking of the great Titanic is, even today, a lesson of humility and reverence.

Throughout the ages, Titanic has been irresistibly viewed as a symbol of a gilded era and a floating microcosm of the Edwardian class system. The caste system on board the famed ship was on full display without any semblance of guilt or political correctness. The steerage passengers, who left their homelands with practically everything they owned, did not mingle with the wealthy passengers, some traveling with their butlers and servants, others returning from leisurely trips from Paris and Cairo. The divisions became even more blatant when the ship started sinking. Despite the myth of “women and children first”, the survival rate for First Class men was comparable to that of Third Class children. Imagining the plight of these men, women and children in steerage, the majority of whom did not speak English, many of them unable to reach the lifeboats, still feels one hundred years after the disaster, uncomfortably raw.

Ironically, the First Class passengers, who included some of the richest people in the world such as John Jacob Astor and Benjamin Guggenheim, became bound for eternity in a heart-wrenching struggle for survival with Third Class passengers who in turn were sailing in search of the American dream. Class divisions were finally erased as death made no distinction between age, gender or wealth. Nowhere is this realization starker than in the Halifax cemeteries where a First Class passenger’s headstone can be found adjacent to that of a Third Class victim.

For Death is the great equalizer.

Finally, the Titanic story transcends all cultures and all ages because it is about human choice. The French philosopher Albert Camus, once said: “Life is the sum of all your choices”. And the Titanic disaster, reminiscent of a Greek tragedy, reminds us that in the face of death, the most sublime and the most wretched of human choices had to be made. The Titanic drama played over two hours and forty minutes, enabling the survivors to witness and give precise and chilling accounts of the excruciating choices people made at the time of the sinking. A few men chose to disguise themselves in woman’s clothing or jump onto a lifeboat as it was being lowered, to escape a certain death. Others, including my great grandfather, hurried a relative or loved one to the safety of a lifeboat. Some men, including the wealthiest amongst them, showed never seen before chivalry and fortitude. Colonel Astor and his pregnant wife gave up their seats on a lifeboat to leave room for a Third Class woman and her child. Mr. Guggenheim chose to dress up in his best suit. The Band chose to play music till the end. Brave women chose to remain and die with the men they loved. Some chose to kneel down and pray.

When facing the horrible certainty of death in the darkness of a wintry sea, Humanity, embodied by hundreds of men, women and children aboard the Titanic, rose to her sublimest height. Colonel Archibald Gracie, a Titanic Survivor, wrote: “There were women in the crowd as well as men and these seemed to be steerage passengers who had just come up from the decks below. Even among these people there was no hysterical cry, no evidence of panic. Oh the agony of it.”

The heroism when hope had vanished and the memorable scenes of human life and death, so intimately connected, yet so incompatible, affirm that Titanic will indelibly remain engraved in our human psyche.

“We are all passengers on the Titanic.”

(Jack Foster, Irish Philosopher)